All the three floors of the museum reflect and respect the original style of the 'folador'.

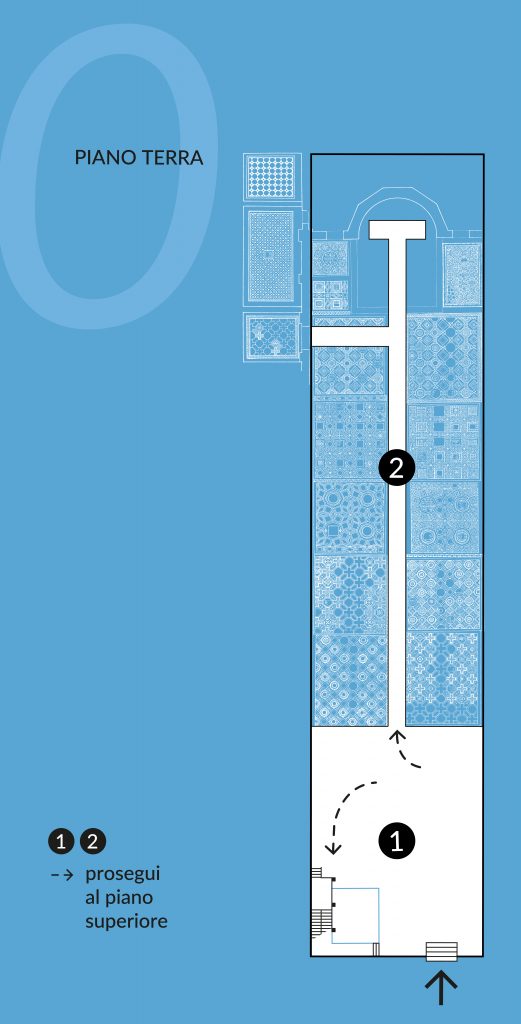

Ground floor

The ground floor of the museum was, many centuries ago, a Paleochristian basilica. The building – 58 metres x 19 metres – has a regular shape. There is a single central nave, a little deep polygonal apse, that is surrounded by a rectangular area, and a lengthened and surrounded by pluteuses presbytery.

A nartece (porticus) with three doors used to lean against the basilica’s façade. In this area, archaeologists found many sarcophaguses, very simple and made of limestone.

The the floor is decorated with mosaics on both sides with a double series of squares. Unfortunately, the central part of the mosaics had been destroyed during the centuries. The mosaics represent many different geometrical motifs. The drawings are perfectly made, by a severe but harmonic hand. There aren’t illustrated motifs, but octagons, circles, squares, and rectilinear and curved elements create an very particular effect. There are also some inscriptions, in Latin or in Greek, that constitute an incredible heritage. First of all, the basilica is the only location where so many inscriptions have been found; secondarily, they tell us the story of a very varied community, with many Latin, oriental and Syriac names. The community who attended the basilica was probably made by merchants or harbour workers and their families, living a simple life – according also to the value of the offers – with a strong faith.

The church, built at the end of the IV century, was really damaged by the Attila attack. Rebuilding the church, they divided the nave into three aisles, adding a new floor on the top of the previous one. Unfortunately, archaeologists were able to save very few pieces of this second floor. They are collected and can be admired on the wall at the bottom of the ‘folador’.

The building was renovated a second time at the beginning of the IX century when the Benedictine monastery was established. There were built arches and columns to support the building, and the floor was made of big stone blocks.

First floor

The first floor consists of a balcony that allows visitors to admire the basilica’s floor completely, in addition to the archaeological finds of the basilica of Beligna- Fondo Tullio (a suburb in the south of Aquileia, towards Grado). This basilica was a cruciform building divided into three aisles, with a semi-circular apse that surrounded an ambulacrum. The walls were divided by square pilasters.

Many mosaics and inscriptions that decorated the basilica’s aisles are now collected in the museum. The apse – with a diameter of almost 22 metres – was decorated with two different mosaics, that were five metres apart. Both the mosaics represent acanthus bushes and vine branches, that interlace and occupy the space. Among the branches, there are twelve lambs and some birds, as a peacock with a wonderful plumage. In the middle of both the mosaics, there was a medallion but unfortunately, they got lost.

The cultural heritage of those mosaics is strongly related to Christianity: the twelve lambs could represent the Apostles or the words of Jesus Christ about the Good Shepherd; the peacock represents immortality, because, in the past, people used to believe peacock’s flesh wouldn’t decompose. The floor inscriptions show that, as happened in Monastero, the parishioners donated money to the basilica to contribute to its building and maintenance.

According to the style of the mosaics and the ornamentation, the basilica was probably built at the end of the IV century. The cruciform shape of the plan, which reminds Christ’s triumph, made archaeologists think it probably was a Basilica Apostolorum, like the ones in Concordia and Milan, and it was built after the Council of Aquileia – September 3, 381 A.D.- against Arianism. In fact, the authority of the Apostles was strongly displayed to fight Arianism and it is believed that, in order to reinforce the faith, some Apostles’ remains were transferred from the East to this church, probably the ones of Andrew and John.

On this first floor, visitors can also admire other prestigious finds, as the inscription of Parecorius Apollinaris, a public administrator, who donated money to the basilica, probably for the renovation of the floor, allowing the basilica to host the Apostles’ remains.

Second floor

On the walls of the second floor, thanks to five wood frames, visitors can admire 103 funerary inscriptions. Those documents are important to discover the history of this area of Northern Italy. On many inscriptions, there are drawings of the dead, often with praying dresses, and of plants and animals, that were symbols of the peaceful afterlife.

The inscriptions’ texts tell us the names of the dead and their relatives and tell us something about their lives, experiences, and their deaths. The inscriptions also allow us to study the spoken language of the period between the end of the IV century and the V one, which could be very different from the written and official one, and to study the culture of the low class and middle class.